Manufacture and Processing

Ingredients:

- Grain

Most often barley, grain was malted (germinated and then dried), crushed, and mixed with boiled water. Once boiled, water is free of live bacteria and thus safe to drink.

Crushed, Malted Barley Being Steeped

|

| Note that the brewer is female. What do you think the mechanism above the pot is? |

- Yeast

Yeast is a fungus which rapidly digests carbohydrates (which grains contain a plethora of) into alcohol. Yeast was not strictly necessary to add to the vat of malt (as grains possess natural yeasts), but it greatly sped up the fermentation, reduced the likely hood of post-contamination, lengthened the shelf-life, and gave control over the consistent product.

- Water

While any amount of water could be used, using too little would have stopped the fermentation process prematurely. Yeast can survive in an environment with an alcohol content up to about 20%, so using too little water would cause the yeast to reach this cutoff too soon and die, rendering a small batch of weak ale, susceptible to contamination.

- Hops

While many people think hops are fermented to make ale, this is untrue. Hops was later added to the process to add a mildly bitter taste as well as help preserve the drink (around 1525 in London). Hops have a natural antimicrobial effect that inhibits unwanted microorganisms.

A Medieval Botanist's Illustration of Hops

|

| 16th Century |

|

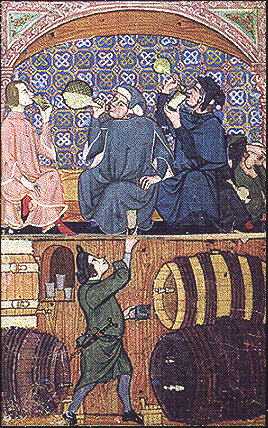

| Now, I doubt these men were just thirsty... |

Alcohol Content

While medieval beers had a lower alcohol content than modern beers, they still resisted contamination quite well. Because the water was sterilized in the manufacturing process, even a small percentage of alcohol could generally keep the drink safe for consumption for up to a week. While it was not common practice to boil simple drinking water, even safe water was easily contaminated through contact with fingers, unclean cups with previously contaminated water, and extended time open to the air.

Souring

While beer kept very well by contemporary standards, it was not immune to time. Given long enough, even the strongest ales would foster dangerous disease-causing bacteria. Interestingly, however, the drink would almost always go sour prior to becoming unsafe to drink. The cause of this souring is a family of benign, hardy microorganisms - lactobacteria. These bacteria convert starches and alcohol to vinegar, giving the drink a horrible taste. While soured ale was revolting to the tongue, it was not yet infected with disease. Thus, before a drink became unsafe, it would sour and be thrown out by the family.